Allgemein

Allgemein

Single Handed Across the Pacific

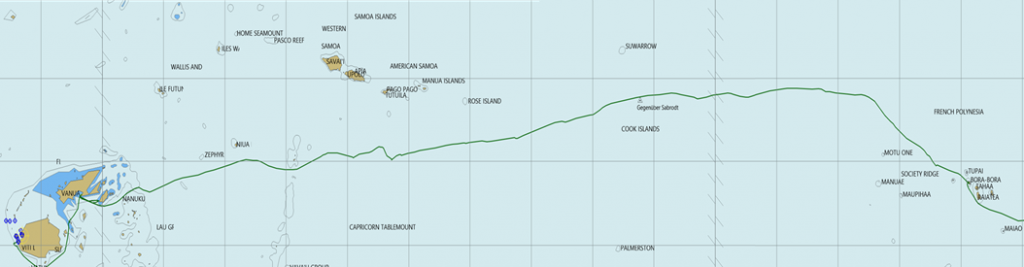

From June 13th to 29th, 2021, I sailed single-handed across the pacific from French Polynesia to the Fiji Islands. The trip passed the Cook Islands, American Samoa, Samoa and Tonga. All these dreamlike islands would be a welcome change on the way to the Fiji Islands. However, due to the Covid19 pandemic, it was strictly forbidden to stop at these islands. So I had to cover the 1800 nautical miles without stopping.

15 days alone at sea bring a number of challenges but also opportunities. In this article you will find out which were important for me and how I spent the days.

What makes single-handed sailing so special?

Challenges and Risks

Loneliness

So far I have been asked most often about the problems with loneliness. Interestingly enough, they didn’t exist in any way for me. I have often been alone for several days in my life. My head is still full of ideas and questions that I can deal with all day. I also have my satellite modem for exchanging e-mails and the InReach tracker for short messages. I received updates from home and support with the weather forecast. So I am not completely alone. Besides that, I didn’t had that much time at all. There is always something to do on board, especially when sailing alone.

No help from outside

The probability of getting stuck on the high seas without outside help is smaller than felt, but by far not zero. Therefore, it is important to think of exactly those things that you will do with two or three people before you take off. Then you can take appropriate measures in order to cope with them on your own at sea.

The obvious thing to do is to include all sailing maneuvers. You should have a plan of how to set the sails alone, how to tack or jibe, how to attach and detach the spinnaker pole and how to reef the sails. Anchoring, mooring at a mooring buoy and mooring at a jetty must also be planned and, as far as possible, rehearsed beforehand.

It becomes more difficult with defects and failures. Anyone who has ever sailed longer distances knows that the problems can be very diverse. Here it is important not only to fall back on your own experience, but also on that of others. You have to have the right spare parts and tools on board and the skills to use them.

Fortunately, I was reasonably fit with my craft before my sailing activities. In addition, over the past two years I have learned a tremendous amount about boat problems in general and the Aurelia in particular.

Despite all the preparation, there is still a large gray area of incidents that one did not think of in advance or could not think of at all. Here it is important to keep a cool head and to improvise.

As a lower safety net there is still the SOS functions of the InReach and the IridiumGo.

The life raft and the EPRIB are the last net. During the preparation I have maintained and tested them. But this last net is so thin that I didn’t want to waste any more thoughts on it after take off.

Little accident – big impact

On the boat it is easy to get a bruise, a swollen knee or elbow. Usually you scold yourself and it will eventually pass. But there are also situations in which you need a helper. This includes injuries from the boom, hanging on the safety line beyond the ship’s side, caring for wounds in inaccessible places and much more. Such things simply shouldn’t happen when you’re alone at sea.

Once again, it helps to keep a cool head and strict serialization and slow processing of all activities. It starts with peeling a potato and doesn’t stop with setting up the spinnaker.

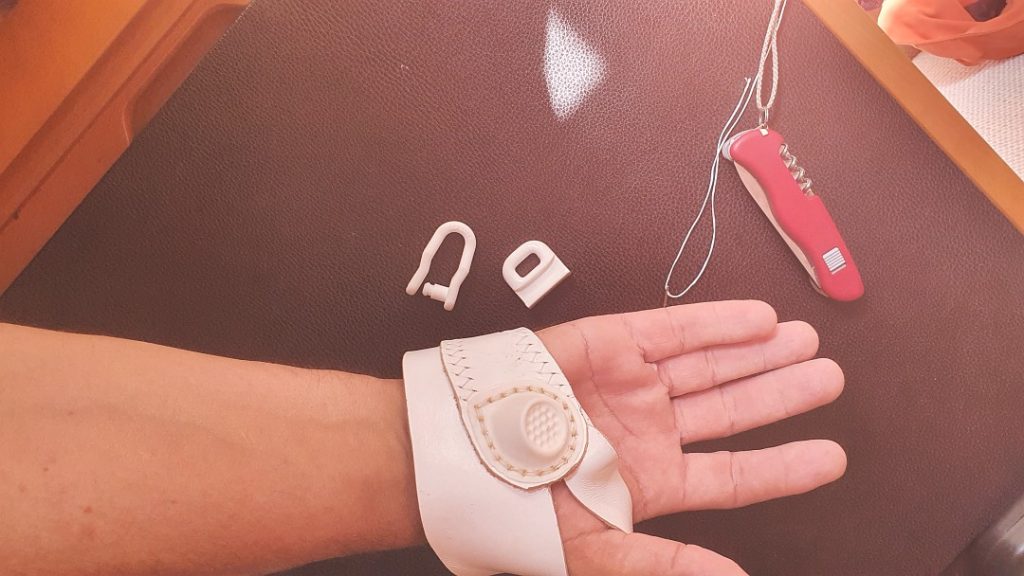

Going over board

It may sound macabre, but it’s a reality. If you fall into the water alone on the high seas, it means certain death in 99.9% of all cases. You are probably more likely to be struck by lightning than to be seen on the high seas. Even with a VHF transmitter, a ship has to get very close to notice you. It is very likely that you can only draw attention to yourself with a satellite beacon on your body. But even then, by the time help arrives, it will probably be too late.

Fortunately, it doesn’t happen that often that you accidentally fall into the water. Due to the finality, however, the only correct measure is: Pick in!

That means: putting on a safety belt or a life jacket and securing it with the safety line at a safe point on the boat. On the Aurelia there are special ropes from the bow to the stern and another safety line around the cockpit table.

The leash-policy applies as soon you are outside the salon. Only when the sea is calm you take it more easy in the cockpit.

The life ring and sling line can be safely stowed away. Nobody can throw them after you. A long floating line that you drag behind the boat is more of a help. With luck, you could grab it and fight your way back to the boat.

Interval sleep

Nobody can be awake for 15 days without a break. Whoever sails alone has to somehow manage to sleep while keeping the ship under control. Very few can imagine how it works. But I could imagine that young mothers feel the same way. On the ship it works – at least for me – as follows:

Whenever the current situation allows it and you are tired enough, you should take the chance to take a nap. To do this, set a timer for a period of time that is appropriate for the current situation (20 to 40 minutes). When the time is up, you wake up with the ringtone. Normally, a few seconds are then sufficient to check the situation. If everything is normal, you fall asleep again very quickly. If the situation has changed, the adrenaline helps you be awake instantly. Often no timer is necessary for this. After all these miles, my body feels and my ears hear when something changes. Even with a crew, I was often on deck faster than the watch could call me.

The electronics on board can also help. My plotter is connected to all of the Aurelia’s sensors. On it I can set an alert for certain threshold values. This includes:

- Strong changes in wind direction or wind speed

- Course deviations

- Collision courses with other AIS vessels

- Shallow depth and a lot more.

I am now quite good at intermittent sleeping. What I still find difficult is sleeping before upcoming events. Even when I’m tired, I find it hard to sleep in anticipation of e. g. bad weather. The result is permanent slight sleepiness. I still need training here.

Chances

But enough of all the things that can scare you. There are also nice and positive sides to sailing alone, for which I am very grateful and happy that I am

Independence

That includes independence. You can go to almost any place in the world without waiting, voting or compromising. This feeling of freedom is a big one for me.

When I began to implement my plan to circumnavigate the world, the wish to sail alone for at least one longer distance was on the list from the very beginning. In the meantime, due to the Covid19 pandemic, more than 3,000 nautical miles I sailed alone. That’s enough for now. I think it’s better to go on a long journey with one or two other crew members or to cover shorter distances with a larger crew. The reason is old and simple:

A sorrow shared is a sorrow halved, and a joy shared is twice as beautiful.

So I think it’s enough for me to know that I could sail alone again at any time if I had to.

Face your fears

There is a high probability that in two weeks alone at sea you will be scared at least once for whatever reason. In my experience so far, there are only three ways out on the high seas:

- You accept the occurrence of what you are afraid of and accept the consequences.

- They are converted into activities that reduce the fearful moment.

- You control your fear through meditative or similar measures.

Which of the three options one chooses depends on the form of fear. In any case, you have to get to the bottom of the cause soberly and objectively. In most cases it helps you to reach your goal successfully.

Here some examples of fear:

- Going overboard: Leash!

- Waves that are too high: Train you during the day, adjust the course at night!

- Too much wind: Download the weather report, train you during the day, reef at night!

- Diffuse fear: Go through the checklist, look at the distance you already sailed, take a deep breath, listen to music, do the laundry!

and so on. This approach not only helps you when you are sailing single handed across the Pacific.

Train your cool head

In a safe environment, you can sometimes afford to lose your coolness. On the high seas this is certainly not very helpful and counterproductive. Of course you know that but in the first few days you have to be aware of this from time to time. When you measure the time of a particular task, you will quickly find out, that you can complete complex tasks very quickly if you plan your steps in advance and then work through them step by step.

There were some good examples of this on my trip, which I will describe below. At the end of the trip, my pulse did not even increase when I moored alone in the quarantine zone with anchor and land lines for the first time.

100% individual responsibility

On land, people like to allow themselves to shift responsibility for an event onto someone else. Since every event happens on the basis of a long chain (actually it is a network) of causes, it is easy to find someone.

Alone on the high seas you learn one thing very quickly: It doesn’t matter who was responsible for the causes. There is only one person responsible for this event, and that is you.

Become one with nature

You don’t fight against mother nature at sea. You talk to her with your sailing maneuvers and she answers with numerous noises and changed ship movements. This is absolutely fascinating for me.

After a few days you almost have the feeling that you have a conversation with mother nature. A few more days and you have the feeling of being one with her. I was amazed to find that at the end of the trip I could tell the instruments whether they were right or wrong.

Unfortunately, I’m afraid that this closeness will quickly disappear again. So far it has always been the case that I quickly get used to a safe stance and calm seas, but need much longer to be able to go to sleep in 3+ meter waves.

New perspectives

Life at sea has its own rhythm, especially when you are sailing alone. It is completely different than on land or on short trips. If you are in this flow after a few days, it is easy to think about your normal life. You can see the forest again and not just a pile of trees. It’s comparable to a good, long vacation, but much more intense.

Clicking on the occasional ad doesn’t make me rich, but it helps me publish my adventures for you.

Shift your own limits

On the high seas alone, everyone gets to know at least one of their previous limits and is forced to change it. Perhaps the clearest explanation for this is with an apnea diver. Normally you want to take your next breath after a minute or two at the latest. With a little training, this time can easily be doubled.

It is similar alone on the high seas. Suddenly you can do things that you didn’t think you could do before. But there is also the other direction: You get to know limits that you don’t want to exceed in the future.

For me it was my limits of concentration, endurance and patience that I was able to exceed more often. Physical exertion is usually also one of them. However, this was very rarely the case on this tour.

I also found limits that I would like to lower down in my normal life. This includes the consumption of calories in general and alcohol in particular.

I burn more calories at sea than on land and still eat less. The result can be seen and felt. I would like to take that with me ashore. But even now, while writing, I notice how difficult it will be.

Alcohol while sailing alone is as good as taboo. I just allowed myself a small beer before sunset. The realization that I wasn’t missing the second one was reassuring and an incentive to leave it at that more often in the future or to do without it altogether.

The trip itself

Weather forecast

Already in the days before my departure I studied the weather report several times. At some point there will be a separate article on this, because there is a lot to explain and report. For this trip, however, I will limit myself to the most important things:

The GFS model shows no gusts between French Polynesia and Fiji. The model does include gust data, but it is never higher than normal wind, sometimes a knot or two lower. This is unrealistic and therefore untrustworthy. Unfortunately, it is the only model available for free via satellite.

The model from ECWMF, on the other hand, is a bit hysterical for my taste and rather shows the maximum possible gusts of a region. You can adapt to this well, even if you rarely get it in reality.

Another observation was confirmed by information from a pacific sailors group. In addition to the equatorial ITC, there is also a South Pacific convergence zone, in which changeable weather has to be expected. The Fiji Islands are exactly in that. Therefore more worse conditions are to be expected, especially towards the end of the crossing.

The current weather report predicts, that the trip will be divided into three parts.

- Good wind and a few big waves in the south.

- A high pressure zone with little wind opens up exactly between Bora Bora and Fiji.

- A strong south-east wind blowing east-southeast of Fiji, which is a bit too strong for me.

So I choose a course that first takes me to the heights of American Samoa. In this way I reduce the time in the doldrums and avoid a large part of the high waves and strong gusts.

Last prep

Most of the preparations were already completed with the arrival of the entry permit for the Fiji Islands. Now it was time to get the dinghy on board. Thanks to the sunny day my batteries were full of charge. So I was able to pre-cook some storm noodles in the evening just in case.

On the morning of June 13th I checked again whether all lines were ready for one-handed sailing. Then I untied the lines from the buoy. It starts!

First days

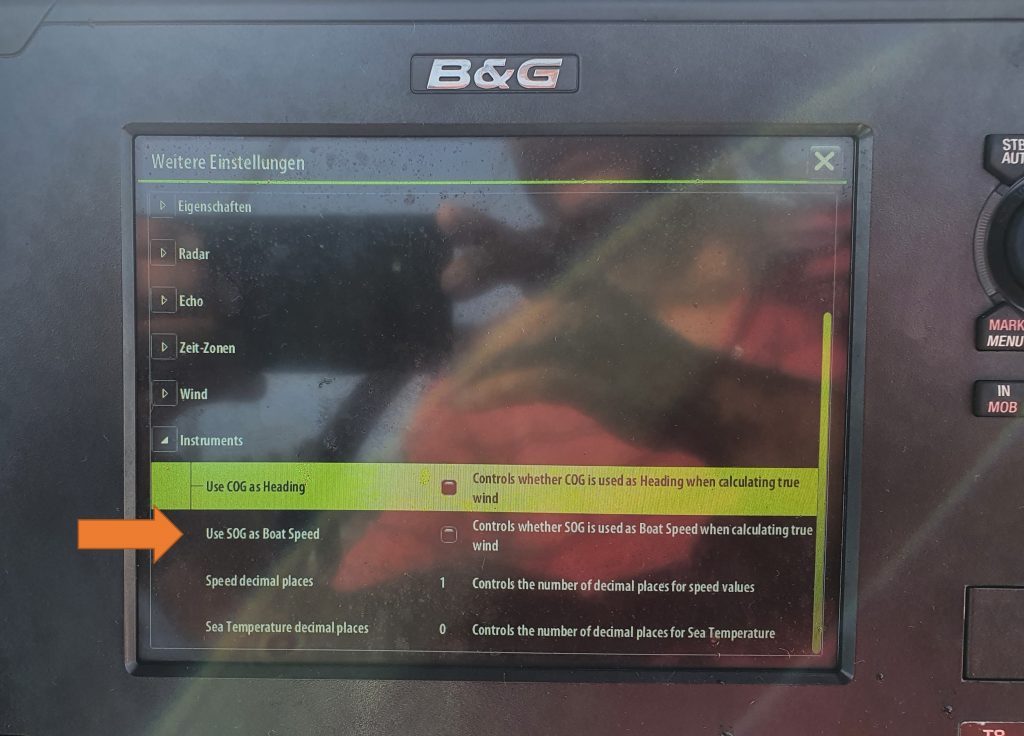

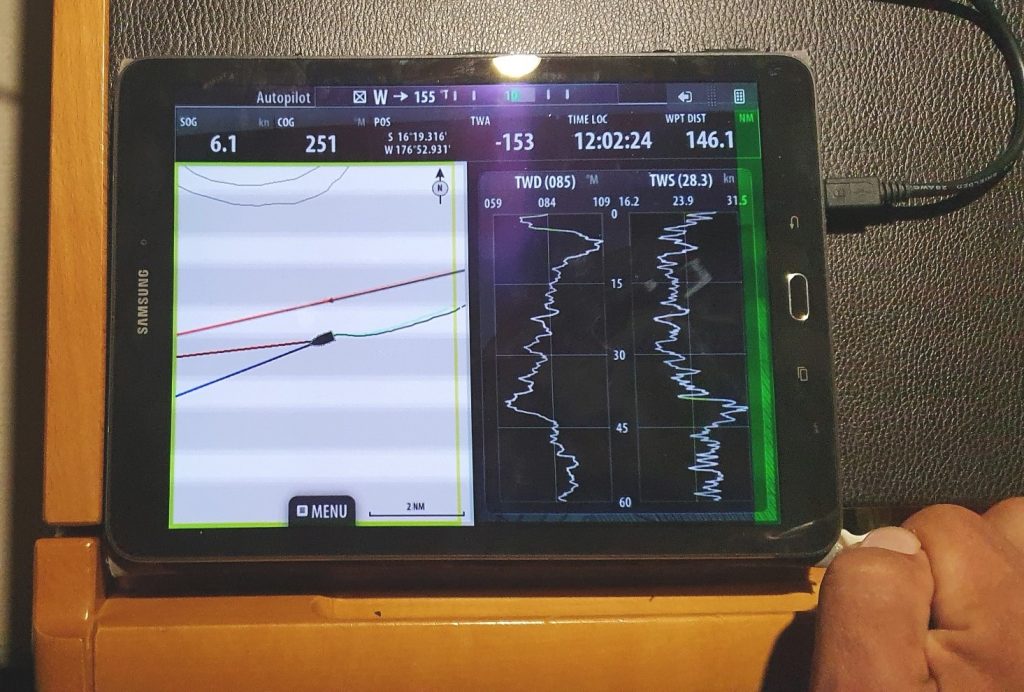

The speed sensor is stuck again

When I made my way to the pass at 7:30 a.m., I quickly discovered that the speedometer was not working despite the underwater cleaning. So there was another threat of false reports from the wind measures TWA, TWD and TWS. Since I had a lot of time after setting the sails, I rummaged through all the settings of the plotter again and lo and behold – you can calculate the values on the basis of SOG. It only took 12,000 nautical miles to find out – better late than never. From now on I am no longer dependent on this little paddle wheel that gets dirty and calcifies so quickly.

Repair on the mast

It rained a lot the first night. Around midnight, after a few gusts, I went to the 2nd reef to be on the safe side. On the second night I had to give up the sole use of the wind vane and accept the hydraulic autopilot. Fast turning gusts around 30 knots were too much for it.

When I went through my inspection the next morning, I found two broken slides on the mast. One of them was old and yellowed. That’s OK. The other, however, was again the one who connects the head of the main sail to the mast. It is sewn to the sail. This will be a major repair – I thought.

First I took down the main sail. Then I put the necessary tools, needle, thread and new slider in my trouser pockets, took a second safety line with me to the front and tied myself to the mast. Since the slides are threaded into the mast below the sail, the entire main sail first had to be removed from the mast. I had not thought about that. So untie again, lash the sail to the boom and than myself again on the mast. Now I was able to do all the work. After just 30 minutes, the main with the new slide started to sail again. That went much faster than expected.

The next few days I achieved a distance of about 120 nautical miles a day. It would have been more if the squalls hadn’t always performed at night. They force me to do an even more conservative sailing setup at night. Below is a small video about one of the few squalls that caught me during the day:

30 hours of doldrums

The days around my birthday on June 19th were characterized by blue skies and shallow seas. Unfortunately, that was also associated with little wind. In the total of four quiet days I had to turn on the engine for 40 hours in order to make any progress. Fortunately, the wind was often abeam so the sails could give at least a little bit of support.

I used the sunshine and the engine time to fill up the water tank, washed all my clothes and some heavily soiled seat covers. Despite all the consumption, there was still enough energy to bake bread and cook a large pot of lentils for the upcoming bad weather period.

The daily checks on the boat discovered only little things. Once the wind vane had locked itself. Another time I found out that the shaft of the Genoa’s sheet block was about to run away again. I fixed them back in place with hot glue. In the next marina I have to find a better solution.

Stormy wind with uncomfortable waves

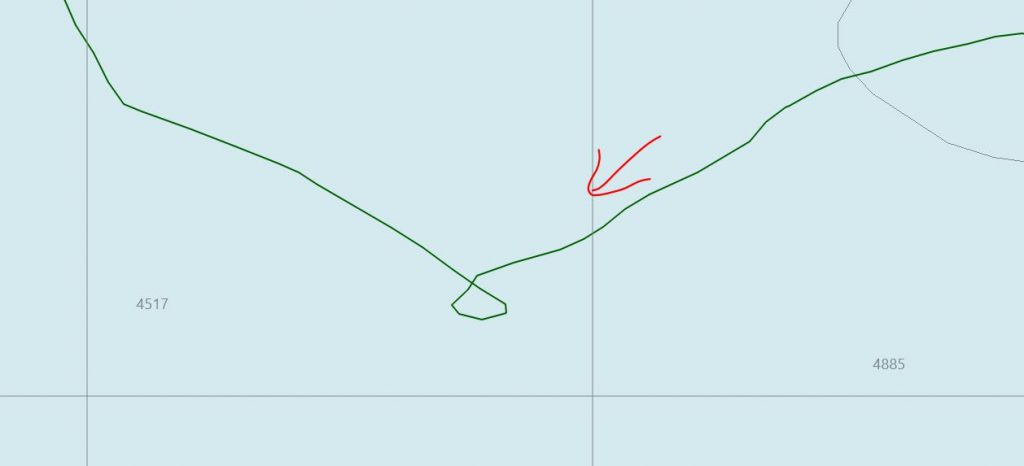

On the night of June 24th lightning on the horizon heralded the end of the doldrums. Then the wind turned south-southwest. The required beating gave the Aurelia and me 6 knots of speed. Then a strange weather situation occurred. Within 80 minutes the wind turned 300 degrees. Without changing the position of the sails, the Aurelia spun in as circle and then found herself on a north-westerly course.

A chain of squalls lay in front of me on the horizon. In some of them you could see lightning from time to time. With a matter of course that surprised me, I put down main sail to pull in the third reef for the first time since I started my circumnavigation. I don’t have a single line reefing system for this third reef. It must be tied by hand. After a few experiments, it was ready for use in time before reaching the squall chain. I found a gap between two of them and quickly sailed through it with some motor assistance. On the other side, the wind and swell gradually increased. After all, they kept reaching values beyond 30 knots and 3 meters in height.

Spray and rain have now soaked all my bad weather clothing. The impregnation (waterproofing) no longer shows any effect. In the wind, it acts like a heat sink. Even here in the South Pacific you freeze as a result. For the more northern latitudes, I definitely have to improve this point. If necessary, all I can do is rub candle wax. Waterproofing spray is not known here.

For the next few days I left the sails on the 3rd reef. In order to ensure more safety and peace at night, I chose a more northerly course in the dark hours. As a result, the wind and waves came more aft. This gave the autopilot more leeway for bad weather and I was able to sleep more comfortably. During the day, I used the stronger abeam wind for a faster journey towards Fiji. So I was able to gradually increase my Etmal to 145 nautical miles.

In between I passed Niuatoputapu. The island belonging to Tonga would be a welcome stopover to wait for better weather. But thanks to Covid19, that is not possible. Once again it has been shown that the pandemic is making life more dangerous not only through the virus but also through our handling of it. To make matters worse, I met a local freighter who didn’t understand me via radio and ultimately forced me to sail closer than I wanted to the nearby shoal. Finally, his AIS gave completely confusing signals. Or was it because of my receiver? Another point for the checklist in the next port.

On the night of June 27, the wind stabilized at around 25 knots. The waves were also slowly waning. But now they came from two directions. Nevertheless, the weather gave me the feeling that I could finally catch up on some sleep. I had just fell asleep really deeply in the second or third interval when a single crazy wave made its way into the cockpit. In a split second, I was wide awake. Soaking wet, I watched as the masses of water quickly drained back towards the stern. Fortunately, the bulkhead to the salon was closed. A few seconds later the bilge pump reported. Somewhere in the cockpit the water found its way into the hull. It was probably only a two-liter, but I would be interested to know which route they took. One more point for the to-do-list after my arrival in Savu Savu.

After a check for possible damages, in which I only found a broken bolt on the swimming platform, I was amazed to find that the event caused me neither fear nor frustration in the crucial minutes. Thant’s good. Only in retrospect I have to say that I don’t necessarily need such situations more often.

Last 250 nautical miles

The weather stabilized step by step. The winds were favorable to aim for the southern tip of Taviuni. From there it goes straight to the bay of Savu Savu, the destination of my trip. Out of some inspiration, I checked the course on a second set of charts. There the area through which I wanted to sail was marked with the remark that there might be unmapped shallows. Great! Presumably this only applies to the immediate vicinity of a reef, but my confidence in the map was gone. I now chose a more northerly course that led me through the official Nanuku passage. To my surprise, this was probably the faster course too.

Clicking on the occasional ad doesn’t make me rich, but it helps me publish my adventures for you.

Date Line

On the night of June 27th to 29th, I passed the political date line. So I will have to live without June 28, 2021 all my life. It is still a little way to the geographic date line, which simultaneously represents the longitude 180 ° west and east. The weather improved noticeably, there were no obstacles in sight – a good opportunity to catch up on a lack of sleep.

A crazy dream

It is certainly not only for me dreams sometimes seem extremely real and you need a few seconds when you wake up to recognize them as such. I will not forget this one in my life and would like to share it with you:

I reached Savu Savu just before sunset on June 29th. Two marinas could be seen. Both had a long wooden jetty, at each end of which was a house with an American-style veranda. On the first veranda, ACDC’s Bon Scott and slow-hand Eric Clapton sat comfortably together. They waved me over.

After docking, we drank a beer together, then they handed me a third guitar and we played Hells Bells first in an extreme slo-mo version. Then the two of them amazed me with their knowledge of a band from my home Silbermond and we and we played “light luggage“.

Then the 40 minutes were over. My timer woke me up. Even now, while writing the blog, I am amazed at how real it felt and how exactly it met the atmosphere that I was later able to experience in reality.

Arrival

With my first coffee, I was still a bit behind the dream. After the second, the focus was back on reality. There are still fifty nautical miles to go. I had 10 hours to get there on time.

The wind let up slowly. I got the most out of my sails and used the engine to help me stay constant above 5 knots.

In advance, I was given strict instructions not to drive into Savu-Savu Bay without permission via VHF. However, the bay is huge and I already thought to myself that nobody would want to talk to me out here. So I didn’t hesitate and drove into the bay.

Only near the warf for freighters and ferries did I assumed a possible radio contact with the navy or the marina and tried my luck. Willi from the Copra Shed Marina answered immediately and asked me to drive slowly into the bay. On the way in, I was met by two navy soldiers and escorted to the quarantine bay.

There two more soldiers opened the floating chain. Two catamarans were already in quarantine behind her. I set my anchor in the middle of the newly dug little bay, backed up next to the second catamaran and handed my two stern lines over to the navy soldiers.

In no time we were finished, as if we had been practicing this maneuver every day, but it was the first time for me and Aurelia. However, while doing so I discovered another loose screw that nearly no more held the eyelet for the 2nd head sail.

Now it was too late for a Covid19 test, which is called “swab test” here. I didn’t care at all. I opened the last beer on board and, after a brief conversation with my neighbors, surrendered to the overwhelming fatigue. With a mixture of pride and relief, I disappeared into my cabin. Without a timer and without alarms, I was finally able to sleep in again.

!!! I DID IT, YEAH !!!!

2 COMMENTS

Great read. Well written and informative. I wished I was younger and be able to do something like this. Oh and wealthier LOL

Great article. Thanks.

Single-handed for 5 years and would have loved to cross an ocean. Unfortunately getting a little old for that!

Wonderful read

Hugh